Naomi Hatfield Allen, an intern with VV from Cambridge University, talks about her days at our CVU in Andhra Pradesh.

I came to Video Volunteers this summer as an intern and am now coming to the end of my two months here. It has been an incredible experience and I hope this blog will give future interns a taste of what life is like in a rural CVU.

(N.B.: A CVU is a community video unit - a local production company run by up to 10 community members. Every six weeks or so the CVU makes a new video, on a topic decided by the community, and then they screen it on widescreen projectors. Find out more about the CVU model here.)

I came to Video Volunteers in order to undertake research for my undergraduate social anthropology dissertation How are Adivasi narratives in the East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh self-created and processed? My focus was to be on representation in the films produced by Manyam Praja Video, an all-tribal community video unit. In order to contextualise this research I firstly watched all the footage available to me in the Video Volunteers office raw footage, rough cuts and finished video magazines from community video units around India. I looked at this film through an anthropological lens, drawing on my knowledge of ethnography and considering the nuances of representation. I wanted to understand:

- Why was this included and not that?

- Why was this shot chosen over that shot?

- Why was that story told and not another?

More academically, I wanted to confront questions concerned with the development paradigm and the ownership of knowledge,

- How participatory is the CVU model in reality?

- How is indigenous/local knowledge incorporated into the work of VV?

After two weeks in the office I traveled to rural Andhra Pradesh and spent a wonderful month staying with the producers of Manyam Praja Video in the remote tribal area of the East Godavari district. I shadowed the producers closely, documenting my experiences on film, in photos and also in detailed ethnographic field notes. This blog is some edited snippets to give you a feel of my time there. Words condense my experiences to a fraction of what they were but I hope this document at least captures something about my stay. It is a mish mash of tenses and tones some sections are straight up descriptions, others are more anecdotal all were written in the field.

Addateegala

The mandal headquarters, a small, sprawling town; the buildings are a mix of mud, wood and palm thatch, and ugly concrete boxes. This mix mirrors closely the towns ethnic makes up, an array of tribals and non-tribals, existing as far as I can see in a quiet disequilibrium walking back from the town to Vanantharam on my first day, Ramea, an articulate local college graduate was telling me animatedly about her community and in doing so referred to tribals and normal people.

Addateegala has a number of garish statues, little schools and innumerable small shops bedecked with sachets of shampoo and washing powder. Cloudy plastic jars are filled with unidentifiable sweets and somewhere at the back a tube of toothpaste nestles next to a stack of notepads. Aside from these general stores there are a number of tailors, sitting peacefully at their peddle sewing machines; sari blouses taking shape in seconds. There are fruit stalls, vegetables stalls, a small pharmacy and a couple of shops selling silverware. The market place, usually deserted, except for the odd stray dog, consists of open-sided, palm-thatched huts arranged in a maze of narrow alleys. On market day (Tuesday) the place comes alive with traders from the surrounding area. The next day, the square deserted once more, the rubbish is gathered into piles and burnt the small ash mounds left to be explored by wild boar.

On most days of the week, action centres around the bus stand and the piece of wasteland (bordered by small shops) that stands in front of it. Here a number of roads meet forming the hub of Addateegala. Share jeeps and autos line up waiting until they are bursting at the seems before setting off to this village or that. The roads are rough and dusty, strewn with litter and manure. Children play, cows and buffaloes stroll, traffic drives erratically and women walk talll, silver water pots balanced on their heads. Water is collected from the many water pumps that pepper the town; they are always busy children, women and even men hauling the lever up and down.

Vanantharam

Vanantharam is a herbal health centre. It occupies a large, concrete, purpose built building approximately 2km outside Addateegala. The building is quiet given its size activity seems at a minimum. This is with the exception of Manyam Praja Video but I will return to them later. The walls are whitewashed inside and out and the interior is adorned with intricate artwork. The centre is nestled in a valley, hills sweeping up on all sides. The building sits in a garden of medicinal plants, its white façade stark against the lush forest backdrop. The road that runs along the front of the centre is quiet, a steady stream of autos, buffalos, the odd jeep and tribals going about their business.

My home for 4 weeks, I am forced to make friends with my unusual room mates the biggest insects I have ever seen, lizards galore and the rat that came for a swim in my toilet. Cold bucket showers provide a welcome respite from the suffocating, muggy heat. Curd and rice cool my mouth after most meals everything about this place is hot the food, the weather, my burnt skin!

The beautiful landscape around Vanantharam

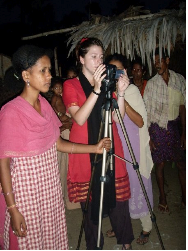

Manyam Praja Video producers

MPV has 9 producers 5 men and 4 women. It functions out of a sparsely furnished room at Vanantharam. The room also doubles as accommodation for the MPV women. They also have a small room next door where they store their belongings in modest metal trunks it is here that they dress, relax, primp and preen but I will return to the domestic lives of these women later.

MPV is divided into two teams that work almost independently

Team A

: Krishnareddy , Saie , Ratna , Kasi, Pothureddy

Team B

: Laxmi , Rajee , Bapuji , Srinu

The teams are further divided Krishna, Ratna, Laxmi and Rajee are seniors and trainers they have been with MPV since its inception (206). They have been intensively trained for over 18 months by Anil Kumar, a Video Volunteer trainer, and are all competent editors. Saie, Kasi, Pothureddy, Bapuji and Srinu have all joined MPV in the last year they are referred to as juniors or trainees. They play no part in the editing process as yet but are all competent at operating the camera. However, none of the above divisions are particularly obvious when the whole team is together. If anything, an as yet unmentioned division seems most prevalent gender. This may be for a number of reasons:

- The women live together and so share a domestic, sisterly bond.

- It is a cultural thing friendships are very gendered women tend to be friends with women and men tend to be friends with men.

- My presence is distorting the women seem eager to absorb me into their world the men less so.

Nonetheless, gender pales almost into insignificance when out in the field everyone operates the camera, argues about lighting and searches out villagers to contribute.

The Field

For me, everything is the field, Vanantharam, Addateegala, the remote villages we shoot in. MPV refer to villages as the field and so in this section I write about my numerous trips to villages.

MPV travel by jeep; a sturdy, open-sided, khaki vehicle that looks like it could deal with any terrain its certainly forced to take on some pretty extreme ones. The villages MPV shoot in are far-flung and remote. I find the distances traveled to record local voices both moving and humbling. Sometimes, when the jeep can go no further we get out and walk, through rivers and paddy fields, across parched earth and over rocky ground. When we reach the villages they are small and consist of mud and wood shelters in various sizes, with palm thatched roofs. These houses are usually ringed by a wattle and dawb fence that encloses a modest outdoor space. This space is typically home to a handful of chicken and also the household stove a mud construction. It is this outdoors space, along with the veranda of the hut, that forms the heart of the home. It is here that women wash and cook, children play and men sit watching the world go by.

These domestic spaces are arranged in a close mish mash rather than alleys between homes, one normally has to walk through the outdoor space of a number of huts to get to homes in the centre of the village. Due to this spatial arrangement there is a feeling of communality and openness. One is never quite sure whom children belong to or who sleeps where.

The overwhelming colour in these villages is a warm, muted terracotta glowing in the scorching heat. A water pump usually stands somewhere near the centre of the village, its concrete surround and metal body the only manmade building materials to be seen. In some villages I didnt see a water pump maybe it didnt exist maybe I didnt find it. Other than a pump, amenities seem non-existent; in some of the larger villages a tiny shop functions out of the side of someones home cloudy plastic jars of sweets and little else for sale I think I have seen this twice.

In Pulusumamidi, Bapujis village, we met his brother. The contrast between them was almost jarring Bapuji dressed in smart flared jeans and bright orange t-shirt, the latest fashion for city kids. His brother, almost identical in face, stood next to him in a faded shirt and traditional lungi. The brothers affection for one another was clear and obviously appearances are only skin deep but I feel the visual difference is worth noting. In Pothureddys village, Simhardripalem, we were entertained by two older women, one of them Pothus aunt. They fed us a traditional tribal drink made from millet and water and we lay out on their veranda. Ratna, stricken with fever, slept fitfully. Saie insisted on a photography session and the village women quietly obliged staring bemusedly into the camera. Also in this village the producers interviewed an old man his face told a thousand stories, weathered by years on the land, his loin cloth hung loosely from his withered frame, a cigar placed casually between his lips. There was something almost timeless about this mans poise, grace and charm. He was warm yet reserved and sat peacefully, his dark, glowing frame arranged awkwardly in the pink plastic chair that he chose to sit in to be filmed.

Domestic Life

Kasi, Laxmi, Rajee and Saie live together at Vanantharam. Their villages are too dispersed for them to commute to work. One of my favourite things about life at Vanantharam is the way in which these women have drawn me into their domestic world whole-heartedly, no questions asked, no holes barred. We wash together, we sleep together; we gossip together, we watch bad TV together. Language is a huge barrier but somehow, through lots of laughter and waving arms we communicate - we talk about boys, marriage and hopes for the future. We paint our nails and dress up in fancy clothes. They painted my hands with henna; I showed them how to where mascara.

My favourite day so far has been friendship day, a gimmicky celebration, similar to Valentines Day but celebrated with great fervour. We awoke and tied friendship bands on each others wrists and flowers in each others hair. We put on our favourite salwars and headed into town for breakfast idli and vada on a banana leaf with amazing coconut chutney. We sat close together on a wobbly wooden bench, the only women in the small, bustling dhaba. They didnt seem to notice the stares and if they did, they didnt care. It was refreshing. Breakfast finished, we headed to the town of Yelaswaram, a two hour bus ride away. On arrival, we headed straight to a cinema hall and even though the film was half way through, sneaked in at the back to watch the rest. The atmosphere was exhilarating, men and women of all ages whooping and jeering, stamping their feet in excitement. The midday sun bore through the corrugated iron roof; I felt I was slowly melting as salty sweat dripped into my eyes making them sting. We sat eating popcorn and giggling, I felt I had known these women for years. The film finished and we surged out onto the street with the other cinemagoers. I didnt understand the Telegu film but it was by far the best trip to the cinema I have ever had.

Retrospective thoughts

Since leaving Manyam Praja Video the experiences I had and people I met have dominated my thoughts. Community media is a new and growing movement. Technology has exploded onto the world stage; it is radically changing the social and cultural landscape; its globalising force is quite staggering. And, it is within this paradigm that Video Volunteers is working tirelessly to empower marginalised communities with a voice to shift the concentrations of power. My time here has been exhilarating, inspiring and humbling. Back in the Video Volunteers office and nearly two months after arriving, the scope of my research has grown exponentially along with my interest in community media I feel in the midst of something almost revolutionary something innovative, radical and vital.

If you have any questions about anything you have read or about what it is like interning with VV, leave a comment and I will get back to you.

Three labourers in Mumbai die after inhaling toxic fumes in a septic tank

The practice of manual scavenging violates Article 21 of the Indian Constitution which guarantees the ‘Right to live life with dignity.’

“12 years of reporting on Caste and Untouchability”

“Over the last 12 years, Video Volunteers has produced more than 600 video reports on caste and untouchability, across India.